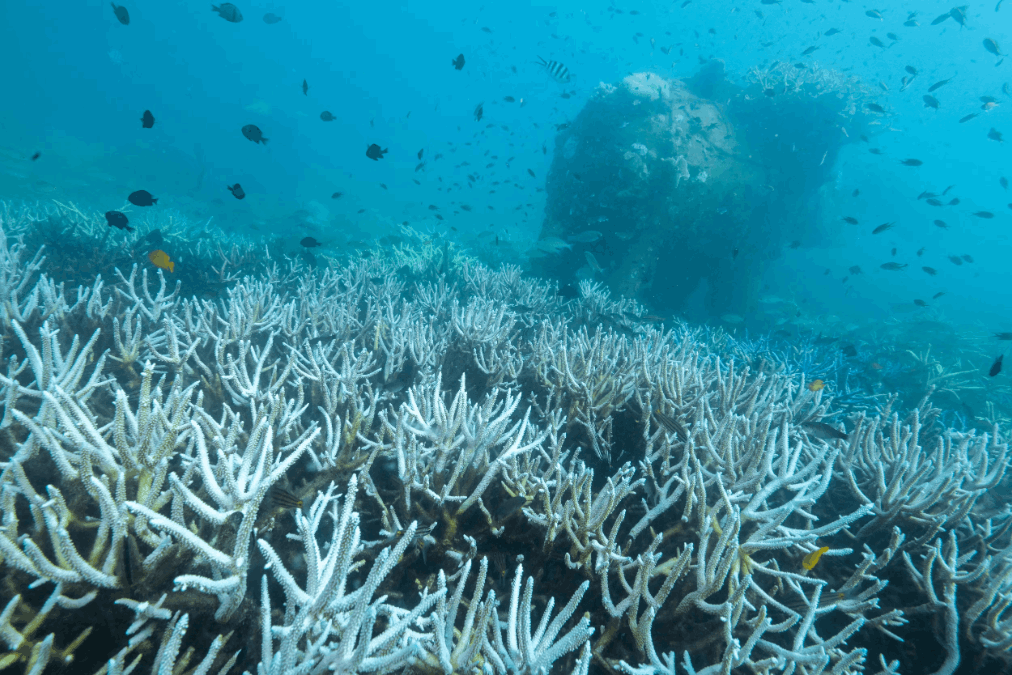

As the global climate crisis intensifies, the world’s coral reefs are facing an unprecedented catastrophe. From 2023 through early 2025, soaring ocean temperatures have triggered the largest and most widespread coral bleaching event ever recorded. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), over 84% of the world’s coral reef areas have experienced bleaching-level heat stress, exceeding all previous global bleaching events. This ecological emergency threatens biodiversity, coastal economies, and the future of marine ecosystems.

The Magnitude of the Bleaching Event

The current phenomenon, now referred to as the Fourth Global Coral Bleaching Event, dwarfs previous events in 1998, 2010, and 2014–2017. While past bleaching events impacted up to 68% of reef areas, this latest episode has surpassed them in both scale and severity. Reports confirm that reefs across more than 80 countries have experienced significant bleaching. Notably affected are the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, the Caribbean, the Red Sea, and the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

In the Great Barrier Reef, Australia’s flagship marine ecosystem, scientists recorded a fifth mass bleaching event in under a decade, with some regions showing coral mortality rates as high as 95%. Remote Western Australian reefs, such as Ningaloo and Rowley Shoals, once thought to be refuges from climate change, have also reported extensive damage.

Elsewhere, regions in the Caribbean—including Belize and the Florida Keys—have seen bleaching and coral cover losses of up to 93%, while parts of the Pacific and Indian Oceans have exhibited similar devastation. Even areas previously considered climate-resilient, such as sections of the Red Sea, are no longer immune.

Why Coral Bleaching Matters

Coral reefs, while covering less than 1% of the ocean floor, are home to more than 25% of marine species. These biodiverse ecosystems support fish populations, provide coastal protection from storms, and sustain the livelihoods of over a billion people globally.

When corals bleach, they expel the symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) that give them color and vital nutrients. Prolonged bleaching leads to reduced growth, reproduction failure, increased disease vulnerability, and eventually death. As corals die, the complex structures they form—homes to thousands of marine organisms—deteriorate, leading to ecosystem collapse.

For humans, the repercussions are severe. Coral degradation affects food security, tourism, and fishing industries. Coastal communities, especially in developing nations, are at heightened risk of economic loss and environmental vulnerability as natural storm barriers disappear.

Climate Change: The Core Driver

The dominant cause of this global bleaching event is the unprecedented rise in sea surface temperatures driven by climate change. 2024 was officially the hottest year on record, with ocean heat content reaching new highs. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has consistently warned that even a 1.5°C rise above pre-industrial levels could jeopardize up to 90% of coral reefs.

Marine heatwaves—now more frequent and intense—are pushing corals beyond their thermal thresholds. This bleaching event unfolded even during a weak La Niña phase, underscoring how anthropogenic warming now overrides natural climate variability.

Responses and Funding Gaps

NOAA has expanded its Coral Reef Watch monitoring system to a five-level alert scale to capture the heightened risk. Despite increased awareness, global funding and policy responses remain inadequate.

While Australia has pledged over $1.2 billion to protect the Great Barrier Reef, conservation groups argue that the investment falls short given the scale of the problem. The Global Fund for Coral Reefs, aiming to mobilize $500 million by 2030, had only secured a fraction of that by mid-2025.

At COP16 in Colombia, the UN issued an urgent call for coordinated global action. However, many reef nations lack the infrastructure or resources to implement large-scale reef management and recovery programs.

Innovations and Hope

Despite the bleak outlook, scientists are pursuing innovative solutions. “Assisted evolution” projects are being trialed, including:

- Breeding or transplanting heat-resistant coral strains;

- Using probiotics and algae inoculation to improve coral tolerance;

- Deploying 3D-printed reef structures to aid regrowth and biodiversity.

Community-led conservation and integration of traditional ecological knowledge are also gaining traction. Coastal communities are working alongside scientists to monitor reef health, implement local marine protected areas (MPAs), and develop sustainable fishing practices.

International collaborations, such as UNESCO’s World Heritage Marine Programme, are helping standardize monitoring efforts and share best practices across borders.

Regional Perspectives

Australia: Mass bleaching events are occurring with alarming frequency. Southern sections of the Great Barrier Reef, once considered relatively safe due to cooler waters, have now succumbed to bleaching. Coral scientists warn that the reef’s fate hinges on immediate and sustained climate action.

Western Australia: Once-pristine reefs in remote areas are now showing signs of severe stress. Footage from Ningaloo reveals ghostly white corals and reduced marine activity—a stark contrast to its previous vibrancy.

Caribbean and Latin America: Coral cover has plummeted in areas like Belize, Honduras, and Mexico. In the Florida Keys, restoration efforts are underway, but scientists caution that without temperature stabilization, such efforts may be futile.

Indian Ocean and Red Sea: Some parts of the Gulf of Aqaba show resilience, but the broader Indian Ocean basin has reported significant bleaching. Researchers are now re-evaluating what constitutes a climate refuge.

Moving Forward: What Must Be Done

1. Cut Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The most effective long-term solution is to curb carbon emissions. Limiting global warming to 1.5°C is critical to preserving what remains of coral reef ecosystems.

2. Scale Up Funding

Global reef conservation needs robust, long-term financing. Public-private partnerships, debt-for-nature swaps, and green climate funds must be scaled significantly.

3. Implement Resilience-Based Management

Expanding and enforcing MPAs, reducing local stressors like pollution and overfishing, and protecting biodiversity hotspots can improve reefs’ chances of survival.

4. Empower Local Communities

Indigenous knowledge and local stewardship are vital. Conservation must be inclusive, giving coastal communities the tools, training, and authority to manage their resources.

5. Advance Scientific Research and Collaboration

Global scientific cooperation is essential. From genetic studies to satellite monitoring, shared data and open-source tools can accelerate effective reef management.

Conclusion

The Fourth Global Coral Bleaching Event is not just a marine crisis—it is a planetary emergency. Coral reefs are canaries in the climate coal mine, their bleaching a warning that the ocean’s health is deteriorating rapidly.

While the scale of the damage is sobering, the tools to avert total collapse are within reach. Whether humanity will act in time depends on political will, collective financing, and our capacity to value nature not just as a resource, but as a vital partner in survival.

The next few years will decide whether future generations will snorkel over vibrant reefs—or only study them in history books.